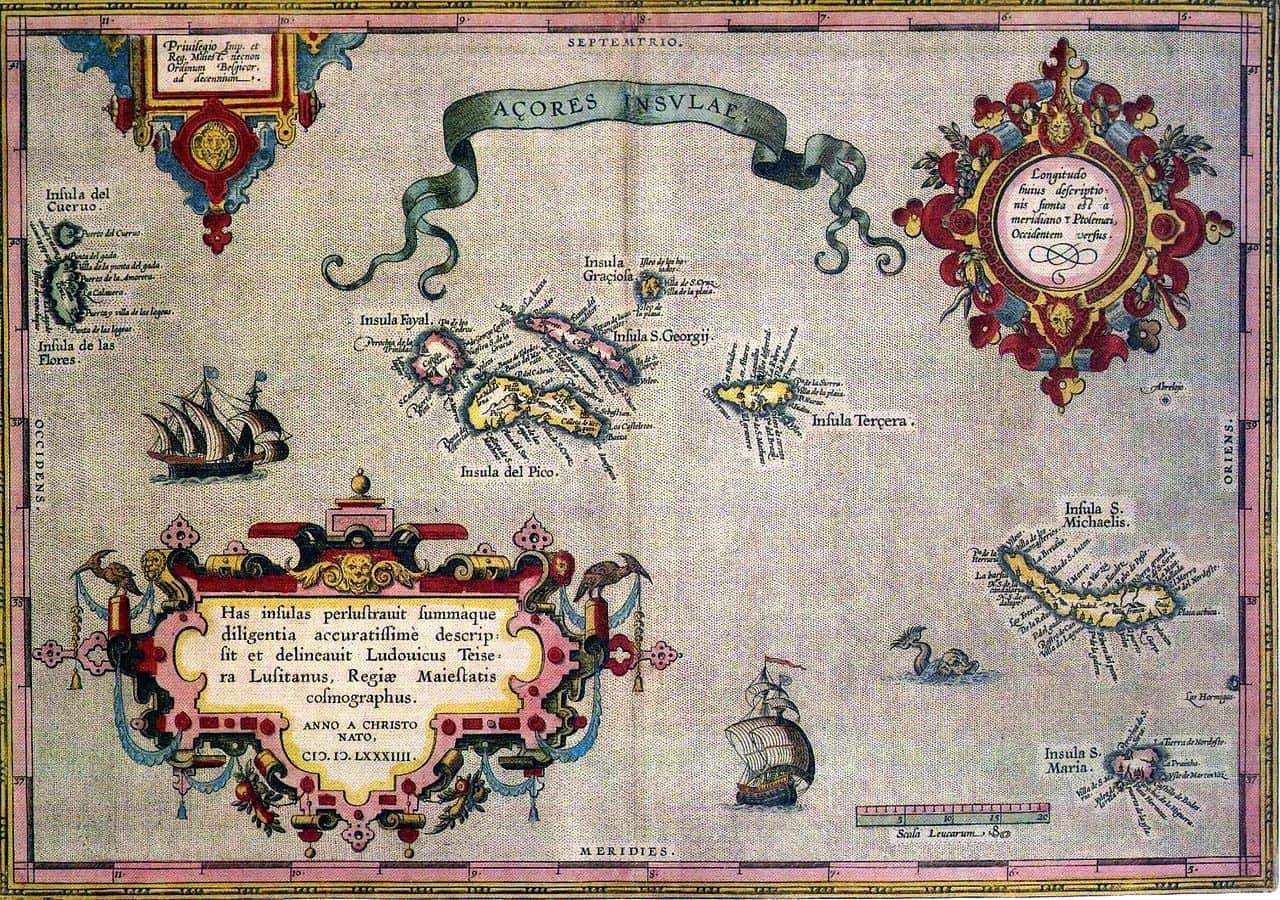

A brief history of the Azores – Part One.

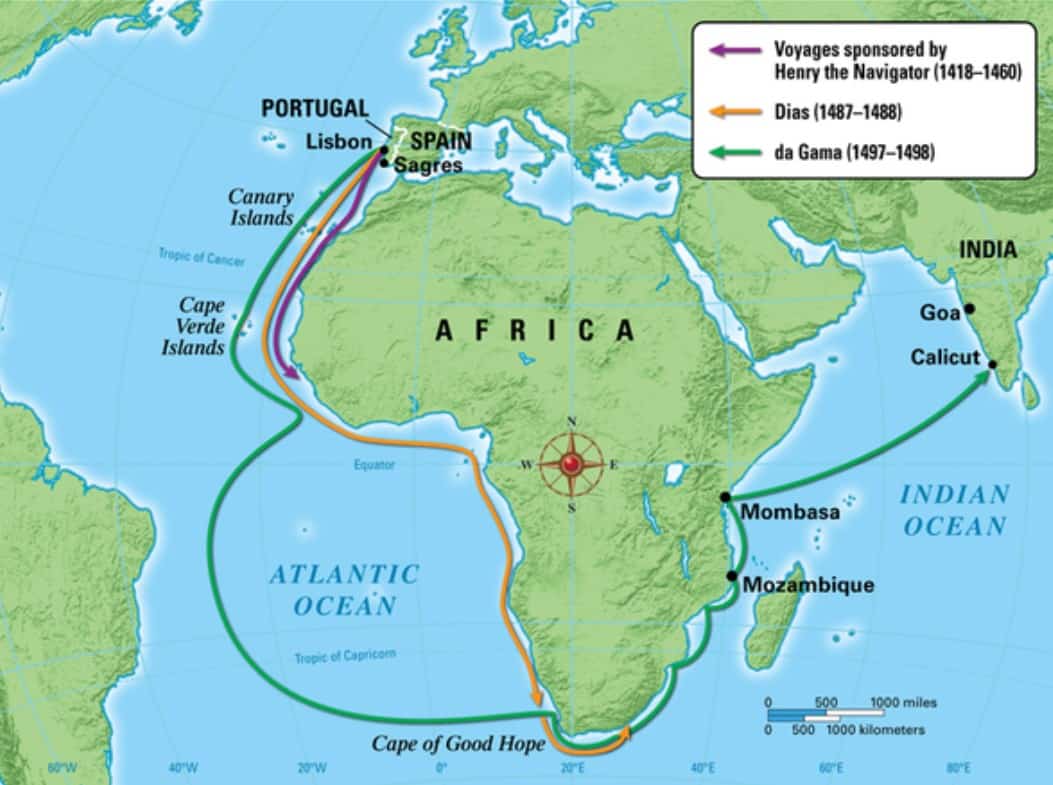

To fully understand the history of the Azores, the best place to begin is in the 15th century when Portuguese ships began exploring the unchartered waters of west Africa.

The 15th and 16th centuries saw Portugal transform from a small fiefdom on the western fringes of Europe to the world’s first modern colonial power. Dom Joao I of Portugal married Philippa of Lancaster in 1387 – Philippa was the daughter of John of Gaunt and sister of English King Henry IV, and their marriage sealed the Treaty of Windsor: the oldest surviving diplomatic alliance between two countries. Philippa’s arrival into Porto is famously depicted in blue Azuelo tiles on the walls of the city’s Sao Bento railway station.

The 15th and 16th centuries saw Portugal transform from a small fiefdom on the western fringes of Europe to the world’s first modern colonial power. Dom Joao I of Portugal married Philippa of Lancaster in 1387 – Philippa was the daughter of John of Gaunt and sister of English King Henry IV, and their marriage sealed the Treaty of Windsor: the oldest surviving diplomatic alliance between two countries. Philippa’s arrival into Porto is famously depicted in blue Azuelo tiles on the walls of the city’s Sao Bento railway station.

Of their nine children, third son Henrique was particularly smitten with the tales of his English Plantagenet cousins and their religious crusades. Henrique’s full title was the Infante Dom Henrique, Duke of Viseu, although he’s more commonly known outside of Portugal as Henry the Navigator.

Crusaders

Follow years of unrest (and with English support), Dom Joao struck a decisive blow against the neighbouring kingdom of Castile and an uneasy truce between the two kingdoms was signed. With a highly skilled army and navy now available, Joao saw an opportunity for his sons to follow in the footsteps of their crusading English cousins. On the morning of 21st August 1415, the Portuguese fleet began their assault on the ‘infidel city’ of Ceuta on the north African coast. Ceuta was quickly overwhelmed and occupied – and remained under Portuguese rule for over 250 years. Henrique distinguished himself in battle, bringing him to the attention of Pope Martin V. He was appointed the grandmaster of the Military Order of the Knights of Christ; the Portuguese successors to the Knights Templar.

Exploration

Henrique’s next crusade against the Moroccan Citadel of Tangier ended in disaster and the near-destruction of the Portuguese army. Part-crusader, part-businessman, Henrique’s attention turned away from religious wars and more towards foreign trade. The Mediterranean trade routes from the far east were controlled by the Venetian Republic whilst the overland routes passed through the Muslim kingdoms of north Africa. Henrique’s captains set sail along the uncharted west coast of Africa – trying to bypass the Muslim Kingdoms in order to connect directly with the rich trans-Saharan trade routes. Never completely abandoning their crusader-fervour, the Portuguese nobility were also searching for viable, navigable routes inland by boat to ‘Prester John’: a legendary figure who ruled over a lost Christian nation (possibly modern-day Ethiopia), said to have descended from the Three Kings.

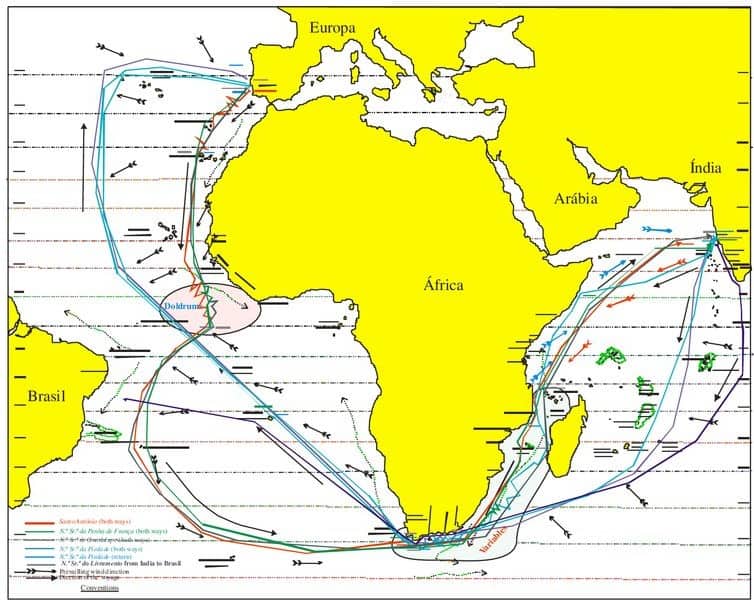

As they extended their reach further south, Henrique’s captains developed a sailing technique known as the Volta do Mar. The prevailing north-easterly winds off the African coast were perfect heading south, but not great when heading north for home. Rather than tacking back up the coast, Henry’s captains found that if they sailed west, out into the mid-Atlantic, they could pick-up south-westerly winds, bringing them back into the north Atlantic and home to Lisbon. Bartolomeu Dias took the Volta do Mar to its extreme when he became the first European to round the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, shortly followed by his more famous contemporary Vasco da Gama in 1497.

The Atlantic islands

Henrique’s captains had mastered the Atlantic trade winds, but there was still a need for Portuguese ships to resupply on their epic explorations.

Madeira

The west coast of Africa itself was often too hostile a place for Portuguese ships to make land. The Canaries, the Madeiras and the islands of the Azores were perfectly placed resupply points. All three groups of islands appeared in various guises on charts of the Atlantic as early as 1373. Being under the control of Castile, the Canaries were not a viable resupply option (although Henrique did succeed in purchasing Lanzarote for a brief period). It wasn’t until 1420 that two of Henrique’s captains, Joao Goncalves Zarco and Tristao Vaz Teixeira, landed on Madeira’s small neighbour Porto Santo and claimed the archipelago for the Portuguese crown.

Madeira was quickly colonised and became the main source of timber for the mainland – and as the forests were cleared, the rich fertile soil and abundant supplies of water allowed the first settlers to grow cereals, wheat and (most significantly for the Portuguese economy) sugar cane.

Santa Maria

Spurred-on by his captains’ successful settlement of Madeira, Henrique turned his attention to the unhabited islands of the Azores. Exact dates are sketchy – we know Henrique was granted permission by his brother the king to begin transporting settlers and livestock in 1439. The more widely accepted story (without an official record) has Goncalo Velho setting sail in 1425 to establish settlements on the two most eastern islands of Santa Maria and Sao Miguel. The village of Anjos (on Santa Maria) is the location of the very first Azorean settlement, with the present-day Vila do Porto being granted town status in 1470.

Anjos and it’s naturally-sheltered bay appear as a historical footnote in Columbus’ exploration of the Atlantic. In February 1493, Columbus was caught in a severe storm whilst trying to return to Spain following his first voyage to the Americas. Searching for a safe haven, they sailed into the Baia dos Anjos – by Columbus’ reckoning their location was somewhere near the Canary Islands and a small group headed to shore in the hope of attending Mass (to give thanks for surviving the storm). As Columbus was sailing under a Castilian flag, they were promptly arrested by the governor of the island and charged with piracy.

Columbus sailed to nearby island of Sao Miguel, to appeal for the release of his crew and to try and repair his ailing ship (the Nina). With the backing of his brother-in-law (Pedro Correia da Cunha – governor of the island of Graciosa), Columbus eventually secured the release of his crew. As a mark of respect, he attended mass in the small Anjos chapel before continuing his voyage. In the centre of the village today, you’ll find a statue of Columbus overlooking the chapel of Nossa Senhora dos Anjos.

Sao Miguel

The colonisation of Santa Maria’s much-larger neighbour Sao Miguel followed, with a first settlement being established on the site of present-day Povoacao in 1432. This eastern-end of Sao Miguel quickly became the agricultural heart of the island, with much of the land devoted to wheat farming and the cultivation of oranges. In the mid-19th century, Sao Miguel was the largest exporter of oranges to the UK and the rolling hills and ‘lombas’ in the east were covered in orange groves. Sadly, a pan-European disease (more widely known as the Great French Wine Blight) decimated the entire orange crop (and most of the Azorean vineyards) in the late 1800s.

Heading west

The colonisation of the archipelago expanded as the settlers ventured further west – establishing settlements on the islands of Terceira and Graciosa in 1450, Faial, Pico and Sao Jorge in 1460, and Flores in 1480. There’s a long gap of a hundred years before the eventual colonization of the tiny island of Corvo in 1580. Together with it’s closest neighbour Flores, Corvo became an important navigation beacon for ships sailing the trade winds between mainland Portugal and her Brazilian colonies. Come the industrial revolution, these westerly islands quickly lost their significance as steam-driven ships transformed Atlantic navigation.

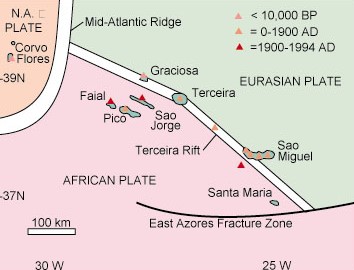

Initially, Henrique had difficulty attracting settlers to the Azores. Setting aside the logistics of transporting axes, shovels, hammers, livestock, seeds, and personal belongings 1400km across the Atlantic Ocean – many of the islands were still volcanically active. The Azores sit on a tectonic plate boundary between the North American, the Eurasian, and the African plates, with the Azores Microplate squeezed in between. Flores and Corvo sit on the western-side of the boundary, whilst the seven other islands are on the eastern-side. The plates are slowly moving apart – increasing the distance between Flores and the main island of Sao Miguel by around 25mm each year (a whole 15 metres since the first settlers arrived).

Help from Flanders

Colonisation of the central groups of islands was eventually spear-headed Flemish émigrés. The Hundred Years War was devastating their homeland of Flanders, making the Azores an attractive prospect for relocation. Terceira’s first Governor (or Captain-Donee) was Jacome da Bruges – a Flemish noble, Jacome brought modern economic theory to Henrique’s court, having learnt his trade in Bruge, the capital of the Hanseatic league. Henrique tasked Jacome, together with seventeen other Flemish families, to colonise Terceira in 1450. It’s estimated that a total of two-thousand Flemish settlers followed Jacome’s lead to relocate to the Azores.

Their influence is still felt today: the etymology of Faial’s capital Horta is said to be a derivation of ‘Huerter’: the surname of Josse van Huerter, the first Captain of the island. On Sao Jorge, the island’s famous cheeses are still produced using the same tried-and-tested techniques of the early Flemish Settlers. Whilst on Pico, Flemish technological know-how built the windmills you can still see dotted around the islands, and the drystone Currais plots which are a key-component of the island’s UNESCO-protected vineyards.

The Carreira da India.

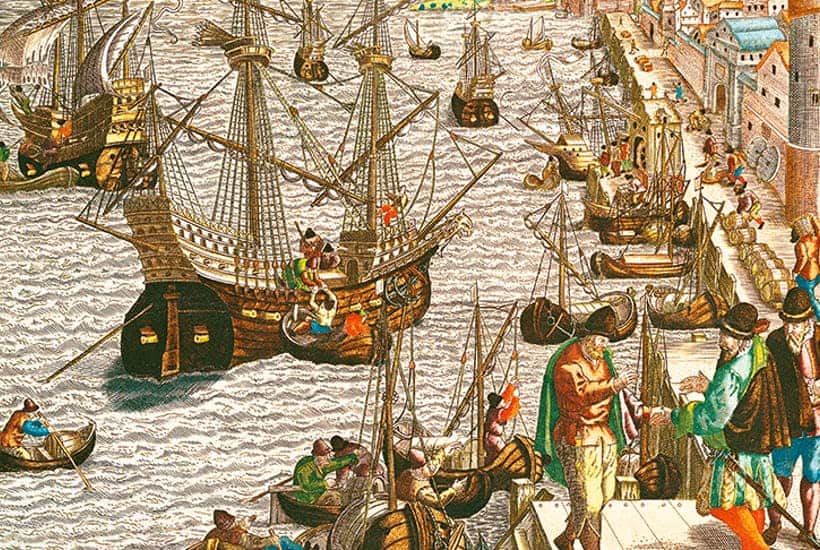

With it’s Azores settlements in place, Portugal began to establish it’s dominance of Atlantic sea trade.

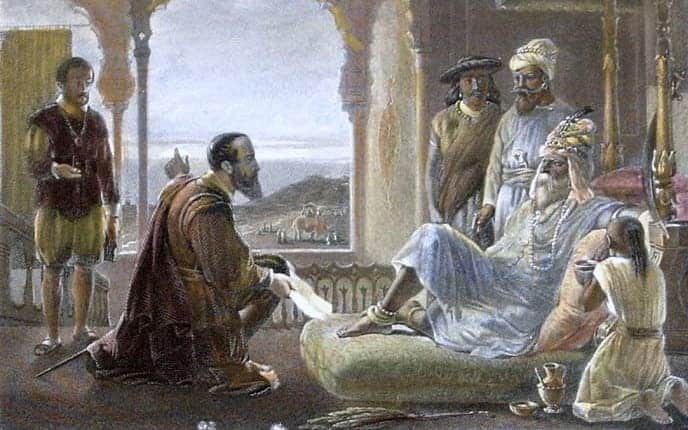

With Bartholomeu Dias having charted the sea route around the Cape of Good Hope, Dom Manuel I dispatched a series of armadas – their mission was to secure treaties with the feudal city states across the west coast of India, and to establish trading posts on Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Africa’s east coast at Sofala and on Mozambique Island. They met with varied success – storms, disease, supply problems, and violence from and against the local populations all took their toll.

Trading posts were eventually established under the control of the Casa da India (forerunner to the Dutch and English East India Companies) which was to oversee all trade. If he could cut the Venetian Empire’s stranglehold, Dom Manuel realised he could monopolise the spice trade – diverting the transportation of pepper, cloves and cinnamon from the established Mediterranean routes via his Carreira da India route, around the Cape to Lisbon.

The sea route to Brazil.

Dom Manuel’s 2nd armada set sail in 1500. It’s intended destination was India but it was immediately beset by storms. Commander Pedro Alvaers Cabral (some say by luck, others feel it was by design) sailed south west in search of more favourable winds (or possibly attempting to reach the Azores to repair his battered fleet). This detour brought them to the west coast of Brazil, making land at present day Porto Seguro.

Dividing the globe.

Spain and Portugal had signed the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1497, drawing a line down the Atlantic between the Cape Verde Islands (Portuguese since 1460), and Cuba and Hispaniola (Spanish since 1492). Lands to the east would belong to Portugal and anything west to Spain (although this was subsequently ignored by the Dutch and English as they began their explorations). Determining they were still east of the Tordesillas line, Cabral formerly claimed Brazil for the Portuguese crown.

The effect on the Azores was almost immediate. Flores and Corvo became crucial navigation points for ships heading home from the Americas, whilst both Terceira and Faial became important half-way houses for fleets to resupply and repair mid-journey. There’s not quite as much modern-day evidence of this period in Faial’s capital Horta as there is in the city of Angra De Heroismo. The grand architecture of the Sé Cathedral, the Câmara Municipal and the Palácio dos Capitães-Generais are all a result of this ‘golden era’, and a constant stream of traders and goods saw the city blossom economically, culturally and architecturally.

A happy by-product of the influx of trade was the introduction of spices from far-flung destinations – perhaps most prominently pepper, cinnamon and star anise which feature heavily in Terceira’s signature dish: Alcatra.

Arguably Angra’s most important building from this period is Solar de Nossa Senhora dos Remedios – known locally as Solar do Provedor das Armadas, or the Manor of the Provisioner of the Armed Forces. The manor was the home of the Ombudsman of the armed forces, whose role was to support and protect Portuguese fleets as they approached the Azores – to bring them safely to Angra and to resupply the caravels with food, water and armaments. Pero Anes do Canto was the first Ombudsman (in fact his full title was Purveyor to the Armada of the Islands and the merchant vessels of the East India trade in all of the islands of the Azores), with his descendants fulfilling the role for three hundred years (up until the 19th century).

Vasco da Gama.

On Angra’s quayside facing the Igreja da Misericordia, you’ll also see a modern-day memorial to this period in Portuguese history – the 2016 statue of Vasco da Gama striding purposefully from the harbour towards the centre of the city.

Gama famously led the first (of thirteen) armadas to India, leaving Lisbon on 8th July 1497. Two years later, on 20th January 1499, they rounded the Cape of Good Hope on their return journey in two ships – the Berrio and Gabriel. The ships became separated in a storm – Gama was on-board the Gabriel and arrived into the Cape Verdean island of Santiago in May. His older brother (and captain of the Gabriel) Paulo was dying of scurvy, and it looked increasingly unlikely he’d make it home without medical attention, such as it was in the 15th century. The Gabriel continued without the brothers, arriving into Lisbon in August (one month after the Berrio). Meanwhile, Gama charted a caravel and sailed with his brother to Terceira. Paulo survived the shorter, quicker journey to the island but passed away within twenty-four hours of their arrival. He was buried at the Sao Francisco monastery, now home to the Museu de Angra do Heroismo.

One of the most important pieces of Portuguese literature is the Os Lusiadas – an epic poem by Luis Vaz de Camoes. Published in 1572, it’s a grandiose, mythologised celebration of Gama’s voyage.

The great earthquake of Vila Franca.

The south coast town of Vila Franca do Campo was once the capital of Sao Miguel – until the great earthquake of 1522.

Vila Franca is born.

Founded in the mid-15th century, the peaceful town of Vila Franca do Campo sits on the south coast of Sao Miguel. With it’s relatively sheltered harbour and central location, Vila quickly became the island’s main sea trading port – and the seat of government when Rui Goncalves da Camara became Sao Miguel’s governing Donatary Captain in 1474. Rui was the second son of Joao Goncalves Zarco – one of the Infante Henrique’s fleet commanders who first settled the islands of Porto Santo and Madeira.

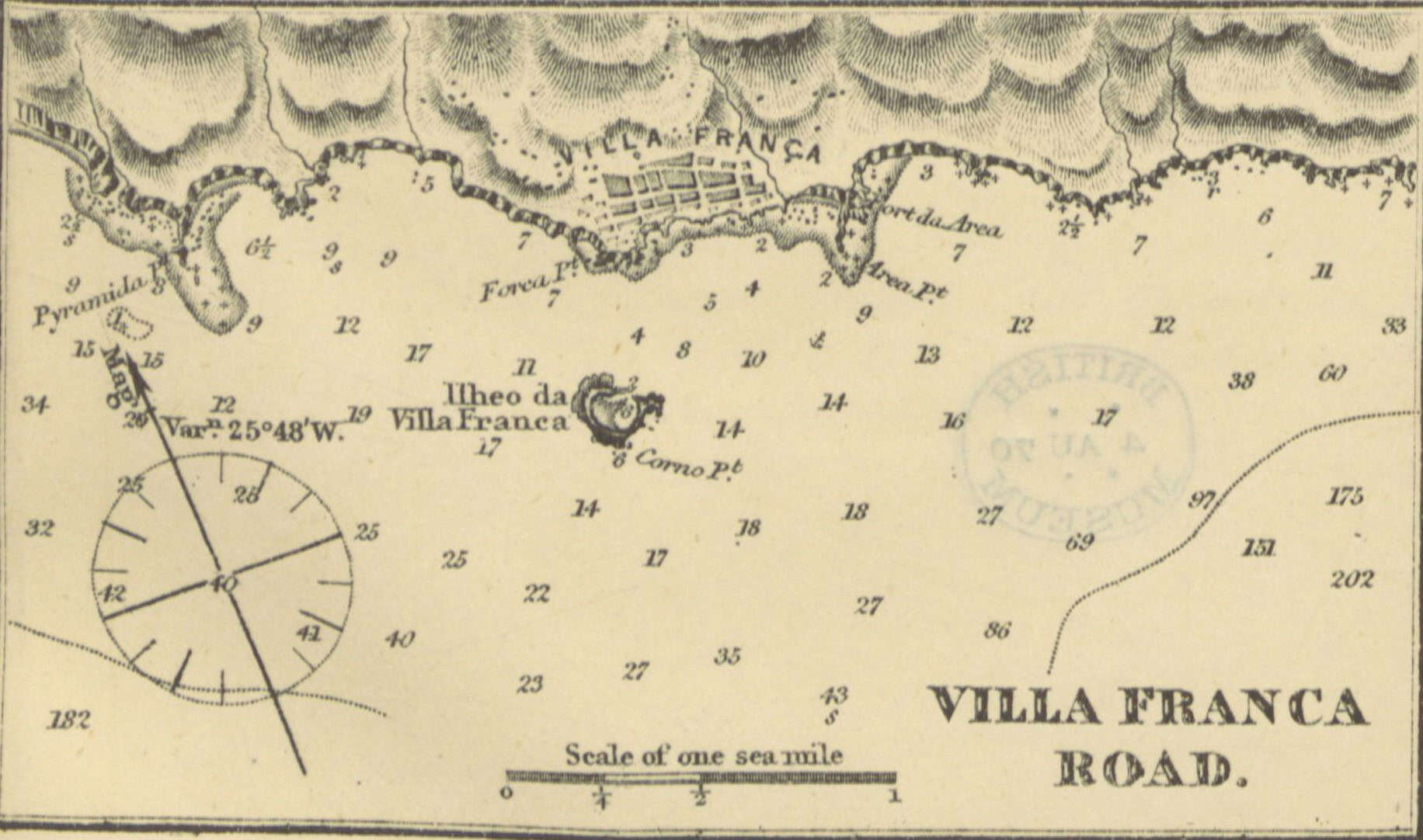

Vila’s location was ideal for expansion – the naturally-protected harbour was easy to locate, thanks to the distinctive Ilheu de Vila Franca: an extinct volcano just offshore, which acted as a easily identifiable navigational landmark for trade ships. Also, Vila was situated on a relatively flat coastal plain which would allow easy expansion to the west, and a readily available supply of fresh water was close by, courtesy of the Ribeira de Agua de Alto and the Ribeira Seca.

However, the quality of the building materials and techniques used by the early settlers was severely lacking. Lime was non-existent on the island, and only the wealthiest households could afford to import mortar (from Porto Santo, a 1000km away). Most buildings were constructed using drystone methods with double-faced, thick walls packed with gravel. The tough basaltic rock was almost impossible to work with the rudimentary tools available to the settlers at the time. The majority of found-stone was rounded and couldn’t be squared, compromising the strength of the masonry. Local clay was also in short supply – again, only the richest settlers and the church could afford tiled floors and tiled roofs, leaving the majority of the buildings roofed with wheat thatch.

Subversao de Vila Franca.

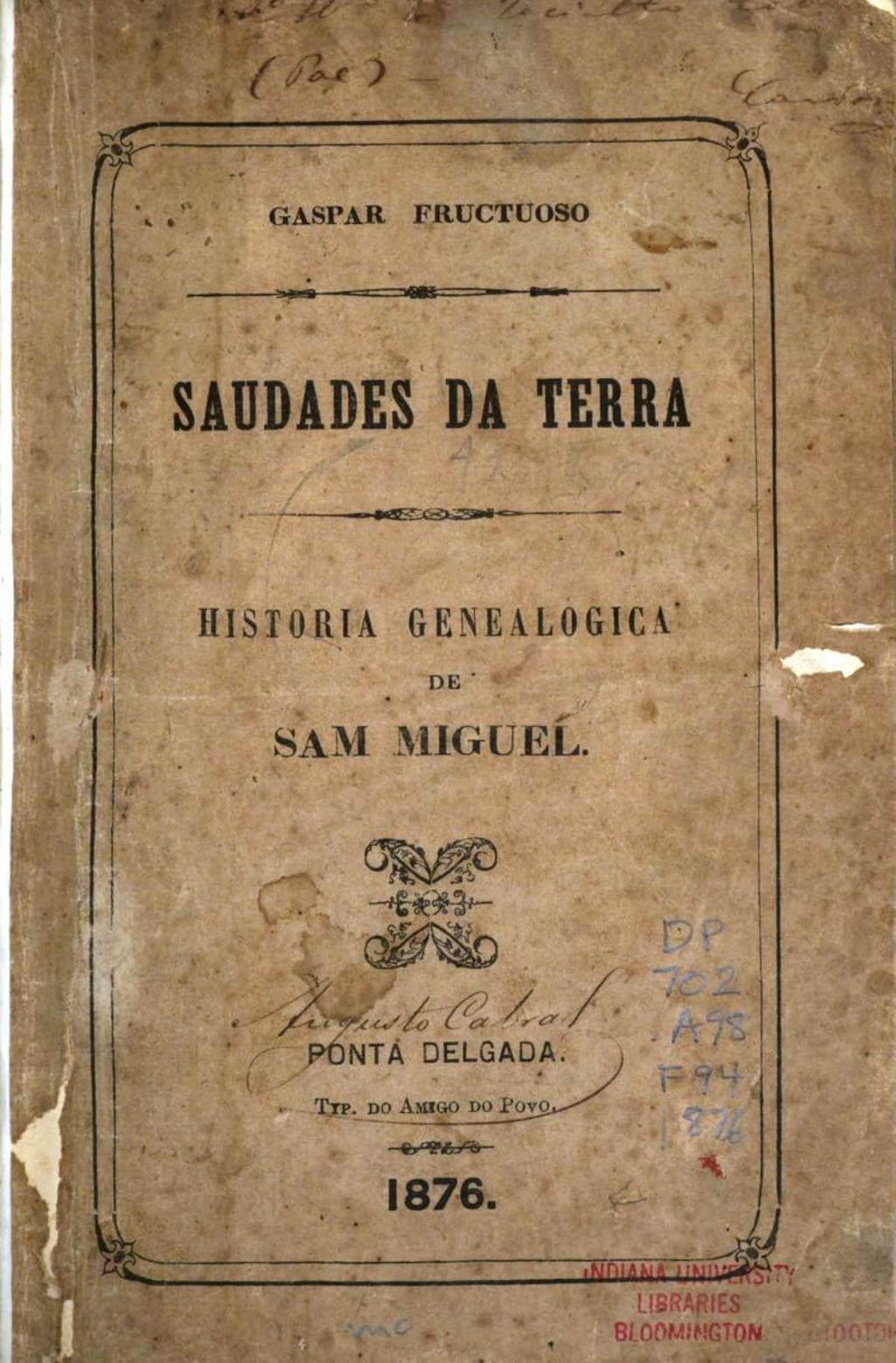

Despite these limitations, Vila flourished as a trading community with no inkling of the tragedy which was to befall the town. In the early hours of 22nd October 1522, a devastating earthquake destroyed Vila utterly – collapsing buildings and burying the town and harbour under a pyroclastic landslide. The only contemporary account this tragic event is called ‘O romance de Vila Franca’ – written by Azorean priest and historian Gaspar Frutuoso.

Born in the year of the earthquake itself (in Ponta Delgada), Frutuoso was an Azorean priest, historian and the writer of the Saudades da Terra: a six volume encyclopedia recording the history, geography, genealogy and day-to-day life of the Azores, Madeira and Cape Verde islands in the 16th century. For reasons unknown, he wasn’t able to publish the Saudades da Terra during his lifetime and the manuscript remained in storage in Ponta Delgada for almost three-hundred years before it’s publication in the late 1800s. It’s now considered one of Portugal’s most-important historical documents. As priest, Frutuoso’s church was Nossa Senhora da Estrela in the north coast town of Ribeira Grande – his final resting place following his death in 1591. A statue at the foot of the church’s steps now commemorates his life and work.

In O romance de Vila Franca, Frutuoso describes nightfall on 21st October as being calm and clear: ‘…Era uma quarta-feira…Quarta-feira triste dia…a em a noite mais serena, nada d’ele se sentia…não corre bafo de vento…estrelado estava o céu…nuvem não o escurecia…’.

‘… It was a Wednesday…Wednesday sad day…in the most serene night, nothing of it was felt…no breath of wind…starry was the sky…cloud did not darken it…’.

The calm would be short-lived – at around two o’clock in the morning, ‘… a huge and frightening earthquake was felt throughout the island…in which it seemed that the elements, fire, air and water fought in the centre of it.. like the waves of a furious sea, appearing to all the inhabitants of the island…which turned it’s centre upwards and the sky fell…during the dawn and until noon on the fateful 22nd of October, the replies were many and hard…’.

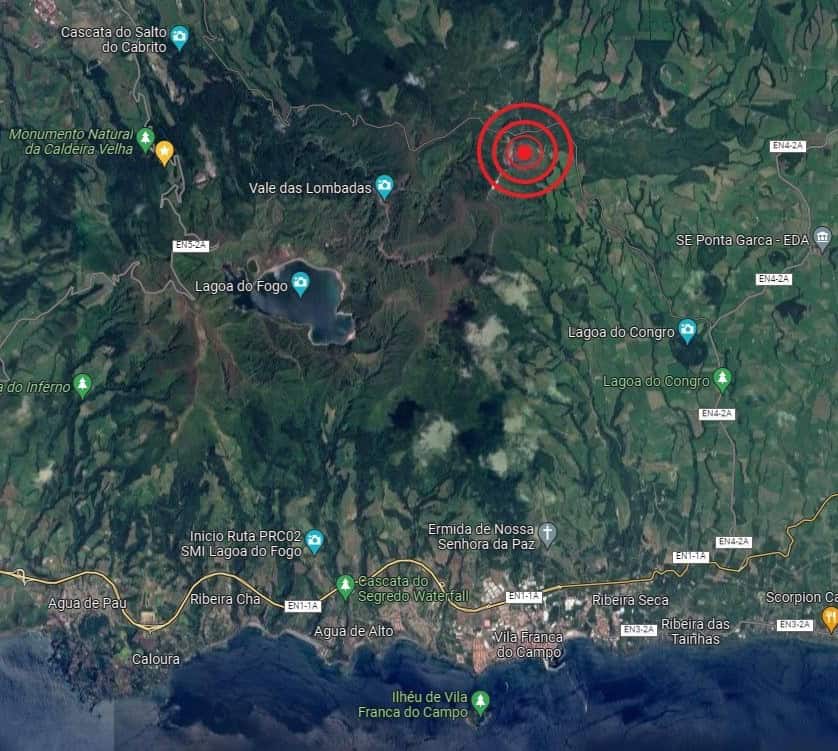

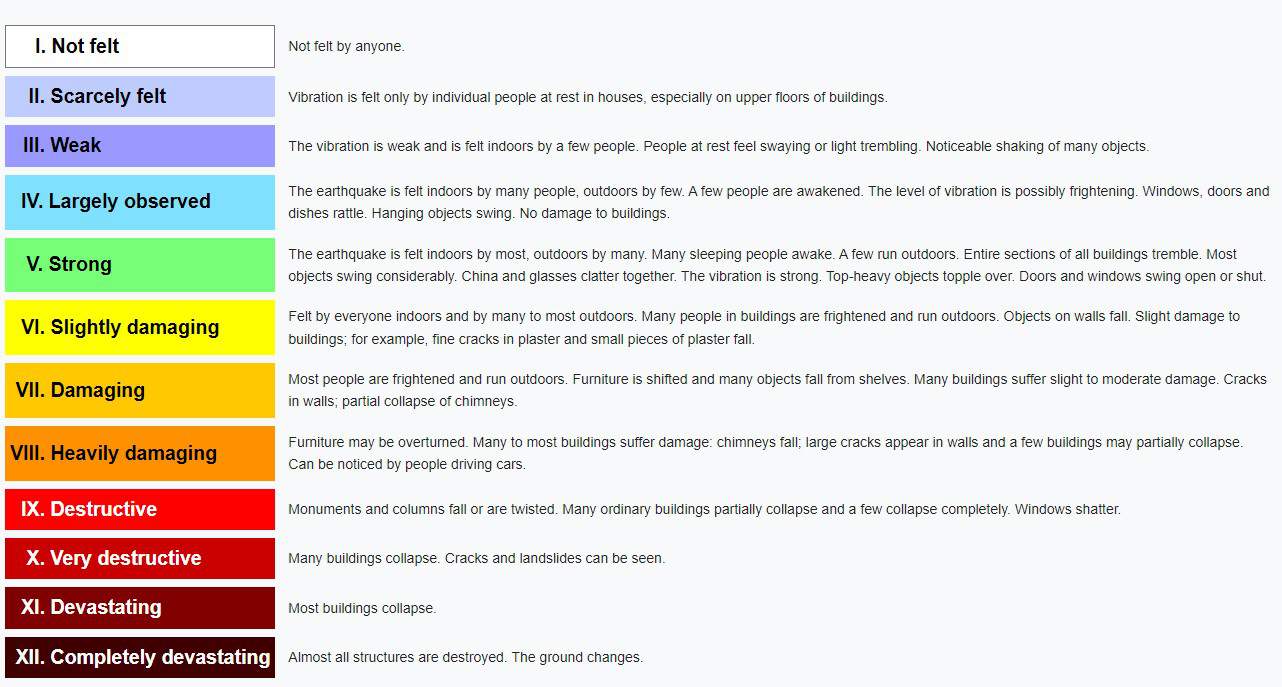

Recent geological studies place the epicentre of the earthquake North/Northeast of Vila Franca, close to modern-day Monte Escuro. It’s also estimated that the maximum intensity of the quake was an X on the Macroseismic Scale – ‘X’ is defined as ‘Very Destructive – most current constructions and buildings collapse completely’, with only ‘XI – Devastating’ and ‘XII – Completely Devastating’ higher on the scale.

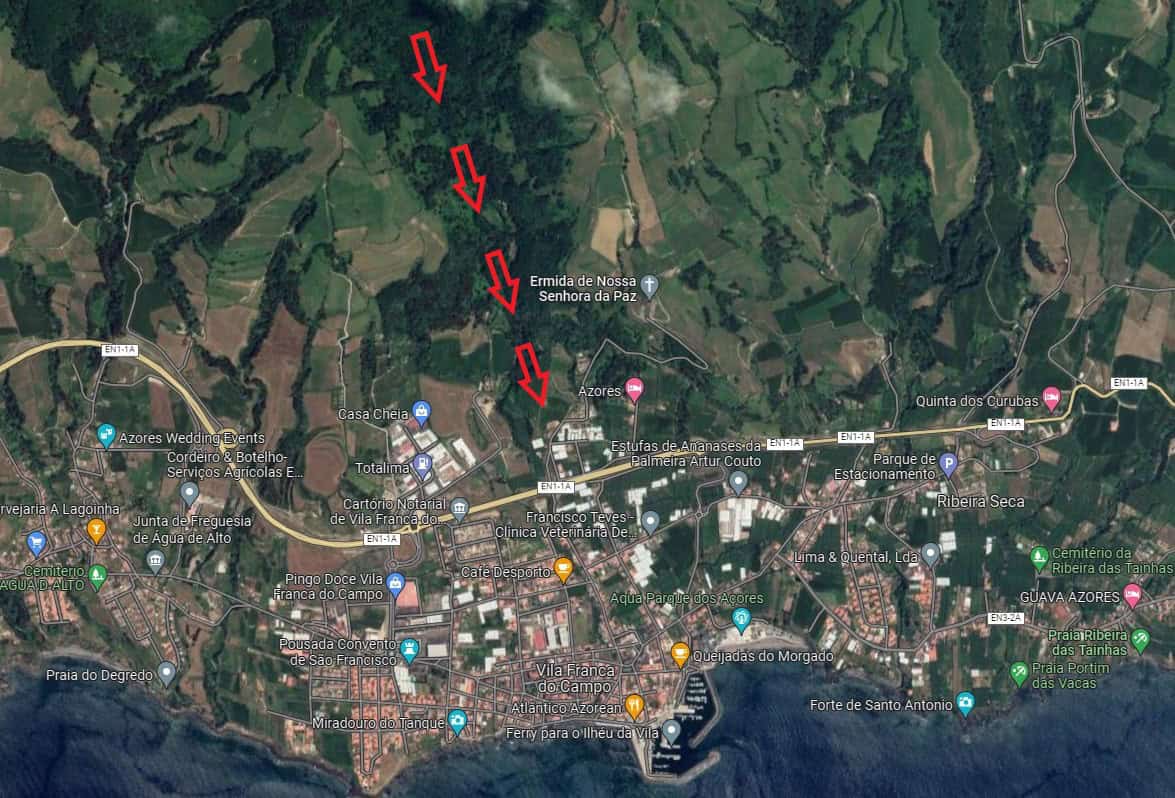

As the initial quake subsided, and unbeknownst to the residents of Vila Franca, an immense landslide had been triggered. Deposits in and around modern-day Vila Franca indicate that the debris originated close to the source of the Ribeira da Mãe d’Água, where heavy rains in the preceding days had softened the low-density, pyroclastic deposits that formed the peak of Monte Rabacal (close to present-day Pico da Cruz). Rabacal collapsed completely, sending an estimated 6.75 million cubic meters water-saturated debris down the Mae d’Agua river valley at a speed of three metres per second, reaching the centre of Vila Franca in a matter of minutes: ‘…from the stream to the east…everything was devastated and the residents were all almost dead…some houses escaped, most of them collapsed…where up to 70 people were left alive… calling for God and others for the blessed Virgin Mary…’.

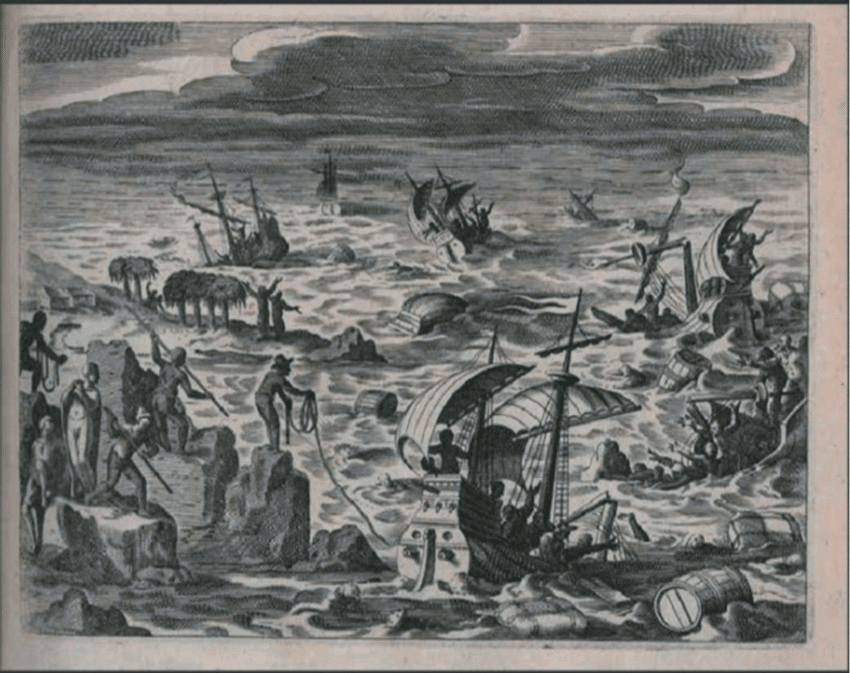

The consequences were tragic: it’s estimated that up to 5,000 people were killed in the town alone, buried under a thick layer of pumice or dragged into the sea by the landslide. The mud mass buried the port and entered the sea, generating a tsunami which destroyed the ships which were at anchor at the Ilheu, drowning the crews and passengers awaiting passage to Lisbon.

‘…there were four or five ships in the port, sheltered on the islet to leave for Portugal, which caused more people to die…where people gathered from all over the island to make that voyage…and when it was already daylight…some people who lived in the mountains and on the farms and those who remained alive in the outskirts…all astonished by the great tremors and roars they heard…and seeing the village in the state it was in, they were amazed…

‘…Many people from all over the island who had their homes there, relatives, friends and acquaintances sent each one to dig wherever they liked…some to remove the bodies of the dead, others to see if they could find money and implements they had in their homes, others to do the same to the bodies and possessions of their relatives and acquaintances…and so they dug up in many parts of the village, and some found dead in the streets and others in their houses and beds, among which they found some alive…

‘…In one tragic night, many lives were ended and everything became covered…of which no noble had houses, nor high buildings, nor sumptuous temples, nor nobles or simple people throughout the morning appeared…becoming everything flat and ground, without a sign or sight of where the town had been.…’.

The aftermath.

The tragedy had a profound effect on the social and geographic development of Sao Miguel. Initially out of necessity, the political and economic governance of the island shifted along the coast to Ponta Delgada, which suffered far less damage during the earthquake. As it became apparent that the damage to Vila Franca was so extensive, the relocation of power became permanent and Ponta Delgada was officially elevated to City status in 1546. It would be another three hundred and seventy years before Ponta Delgada officially became the capital of the Autonomous Region of the Azores in 1976.

The ‘Subversao de Vila Franca’, as the earthquake became known, is one of Portugal’s worst natural disasters, second only to the Lisbon earthquake of 1755. 22nd October 2022 will be the 500th anniversary – the day is to be marked with a series of seminars in Vila Franca on natural disasters in history through the lens of natural sciences, evidence of catastrophic events in the archaeologic record, and the impact of natural disasters on social, economic and political dynamics.

The Crisis of Succession.

You can roughly divide Portugal’s complex history according to her rulers:

1385 to 1580 – monarchy rule by the House of Avis.

1580 to 1640 – monarchy rule by Spain (the House of Habsburg).

1640 to 1910 – monarchy rule by the House of Braganza.

1910 to 1926 – the Primeira Republica Portuguesa (the 1st Republic).

1926 to 1974 – the Estada Novo dictatorship.

1974 to date – democratic republic and member of the European Union (1986).

The final years of the House of Avis were a golden age for Portugal and particularly for the Azores. A series of armadas in the late 1400s had established the Carreira da India – the sea-route from Portugal to India. Due to the islands’ stragic importance as a resupply point, the Azores became one of the cornerstones of the country’s economy. As kings of a worldwide empire, Dom Joao III (reign: 1520 to 1557) and his successor Dom Sebastiao I (reign: 1557 to 1578) were both conscious of the threat pirates and privateers posed to the Portuguese fleets, their vulnerable ships heavily-laden with treasures and spices from India and the Orient.

Italian military engineers Tommaso Benedetto and Pompeo Arditi were hired to draw up defensive plans for the islands of Sao Miguel, Faial, and Terceira. On Sao Miguel, the Forte de Sao Bras still dominates the quayside in Ponta Delgada, as the command post of the Military Zone of the Azores.

Whilst on Faial, the Forte de Santa Cruz was saved from ruin in 1969, becoming the Pousada da Horta hotel. This fort is worthy of a blog in it’s own right – it has a particularly interesting history involving Sir Walter Raleigh (in 1597), and the largely-forgotten War of 1812 between the USA and UK.

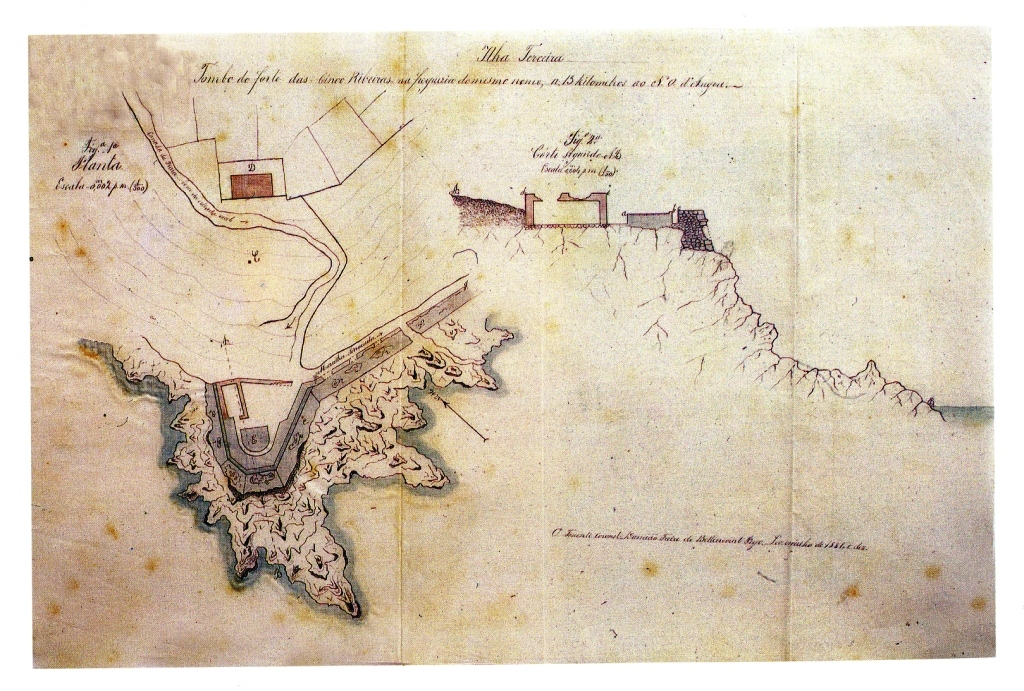

Protecting Terceira.

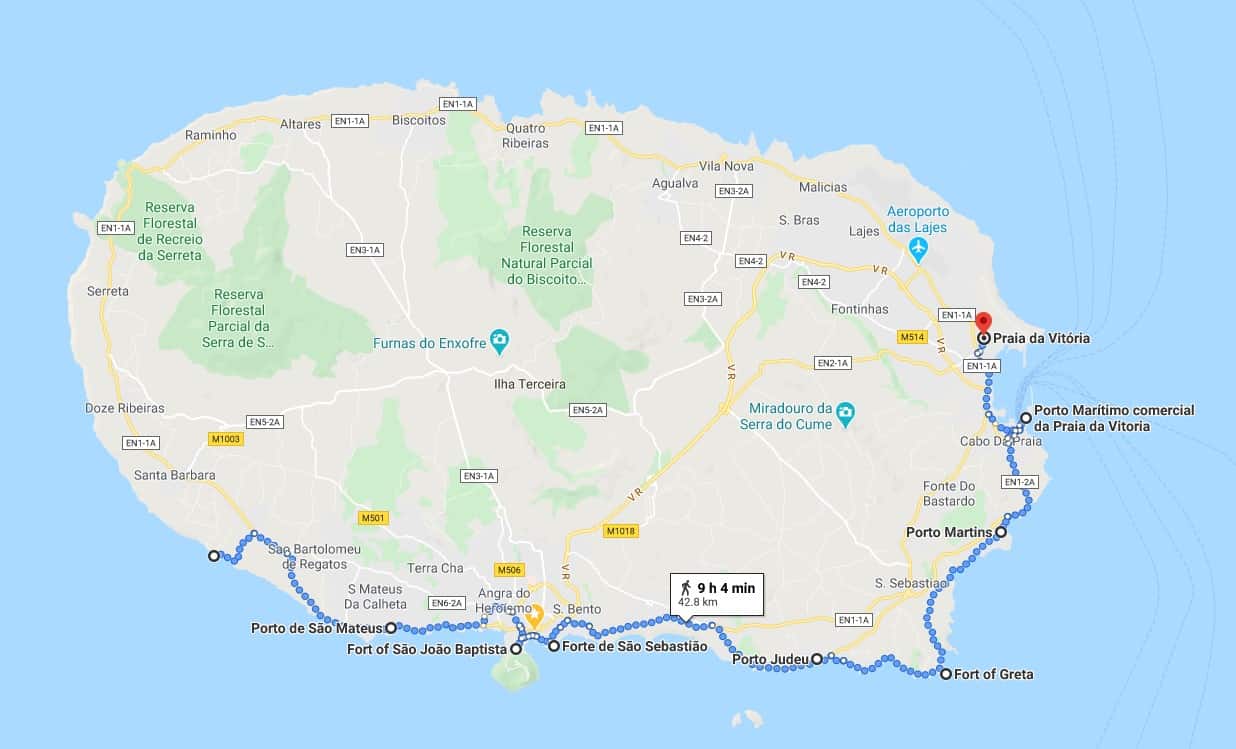

But it was Terceira where the most formidable defensives were constructed. Favourable winds and sea currents made Terceira the island of choice for most trade ships – an ideal resupply point before making the final push home to Lisbon.

An impenetrable line of fortresses were built along the island’s south coast, protecting the most-crucial anchorages – from Porto das Cinco Ribeiras in the west to Praia da Vitoria in the east. It’s quite a list: the Forte das Cinco Ribeiras, Forte da Igreja, Forte Grande, Forte das Mare, Fort da Ferramenta, Forte de Negrito, Forte do Acougue, Forte das Cavalas, Forte do Caninas, Forte das Mos, the Forte de Sao Sebastiao and the Forte de Sao Joao Baptista.

Terceira’s forts now sit in varying degrees of ruin, their heavy walls long-since recycled as building materials for homes on the island, although traces can be found if you know where to look. Some have even been repurposed and are now popular swimming spots.

Two of the best surviving examples are in Angra itself, overlooking the city’s main harbour: the Forte de Sao Sebastiao and the Forte de Sao Joao Baptista. Like the fort on Faial, the ruins of the Forte de Sao Sebastiao were converted (in 2006) into one of the island’s most popular hotels: the Pousada da Angra.

The Forte de Sao Joao Baptista sits just across the bay, on the flanks of the extinct Monte Brasil volcano. It’s military role never ended, although today the fort is more a national monument of historic importance than a base for the armed forces.

The fall of the House of Avis.

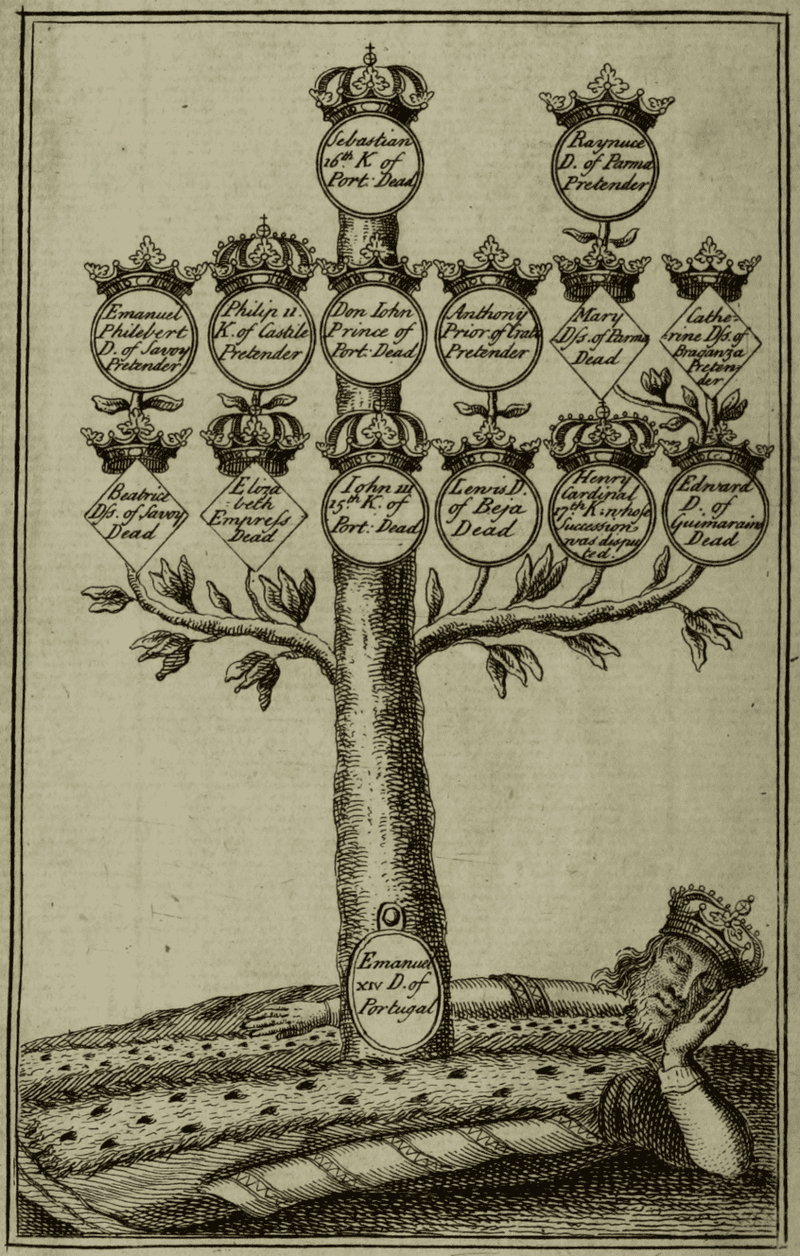

Dom Sebastiao I continued with the construction of the fortresses when he succeeded his grandfather as king in 1557. He never married, never had children, and died at the disastrous Battle of Alcacer el Kebir in 1578, aged 24. Leaving no direct heir, the crown was passed to Sebastiao’s great uncle Henrique.

Aged 66 and in ill-health, Henrique understood the need for an heir in order to maintain Portugal’s independence from it’s powerful Iberian neighbour Spain. However, Cardinal Henrique’s Holy Orders and his vow of celibacy prevented him from taking a bride. He passed away heirless on his 68th birthday in 1580, plunging Portugal into a crisis of succession.

King Felipe II of Spain becomes King Filipe I of Portugal.

With no clear line of succession, the throne was initially claimed by Antonio, the Prior of Crato – the illegitimate son of Henrique’s brother Luis.

However, King Felipe II of Spain believed his line of succession was stronger. More widely known here in the UK for the Spanish Armada of 1588, Felipe was the son of Henrique’s elder sister Isabella and the powerful Charles V of Spain – head of the House of Habsburg, and ruler of an empire which included Spain, Italy, the Netherlands and most of present day Austria and Germany. When Felipe ascended the throne of Spain in 1556, he strengthened his claim to the Portuguese throne by marrying Dom Joao III’s eldest daughter Maria Manuela.

Antonio was proclaimed king on 19th July 1580, but his reign would be short-lived. As ruler of the Habsburg Empire, Felipe commanded one of the strongest armies in Europe, whilst the Portuguese armed forces had never fully recovered from the Battle of Alcacer el Kebir. Spanish troops landed at Cascais and marched on Lisbon, supported by an armada on the River Tagus. Antonio’s army was decisively defeated, and King Felipe II of Spain was crowned Dom Filipe I of Portugal.

Pretender to the throne.

With mainland Portugal lost, Antonio fled to Terceira, protected by Dom Joao III’s impenetrable network of fortresses. He established a government in opposition to Dom Filipe’s royal court in Lisbon – however, his rule was only recognised in the Azores. Through financial incentives and the promise of Portugal’s continued autonomy, Dom Filipe had already gained the support of the Portuguese nobles and high clergy. He was recognised as the official king and Antonio was proclaimed pretender to the throne.

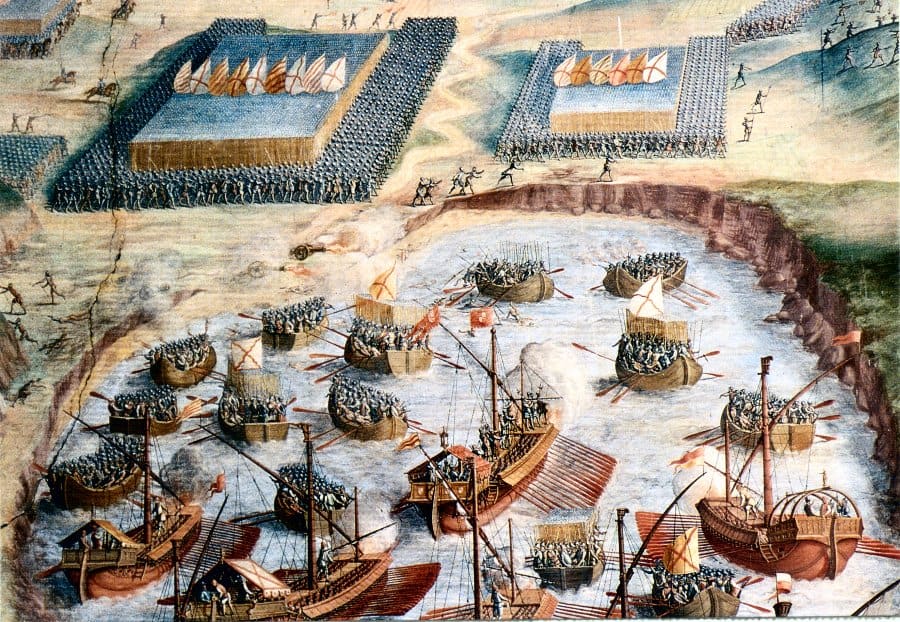

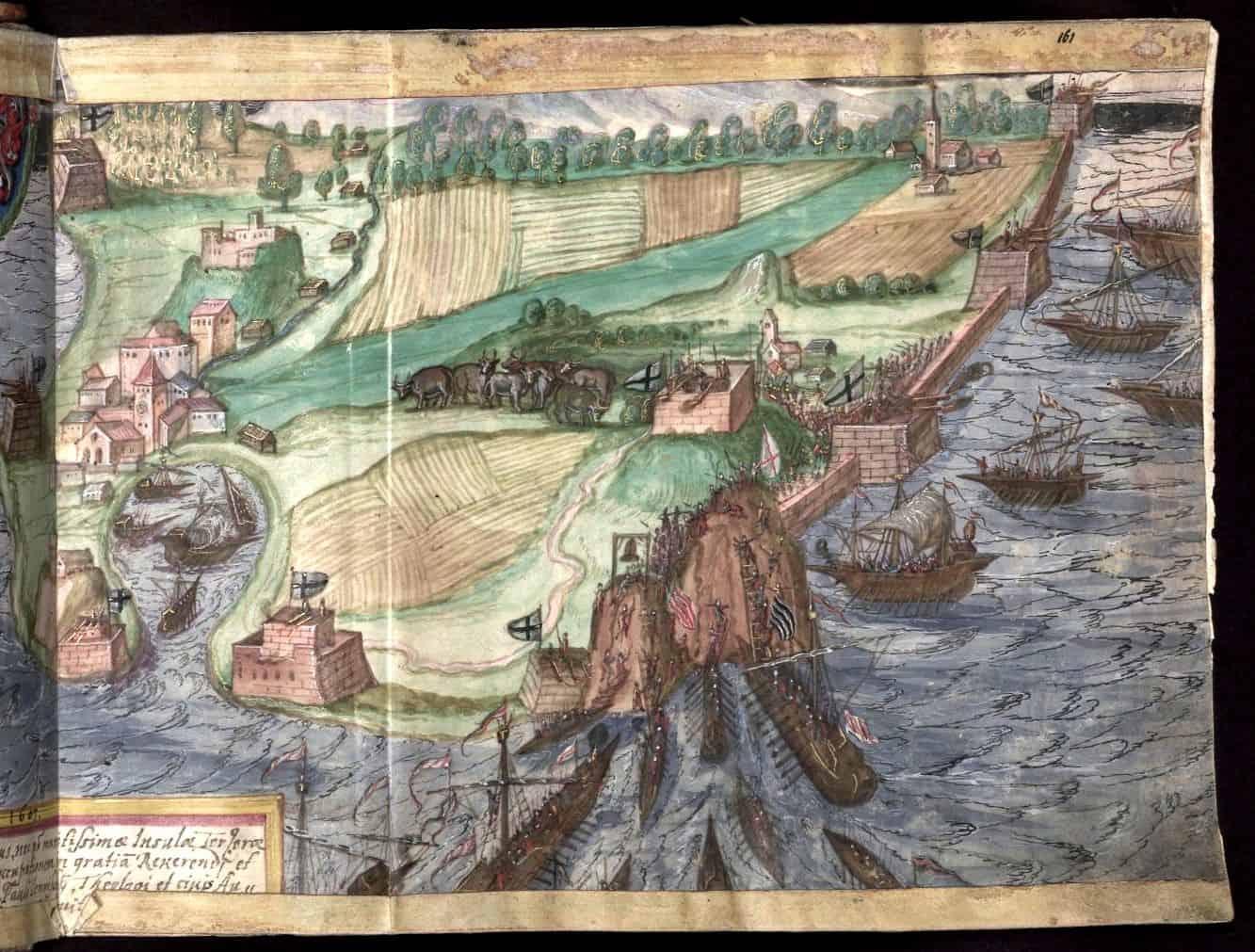

In exchange for their support, Dom Filipe offered the Azorean nobles an amnesty, which was accepted by the inhabitants of Sao Miguel and Santa Maria but rejected by the other six islands. With support from a French fleet, Antonio set sail to subdue the two islands – meanwhile Filipe dispatched his own fleet with the intention of assaulting Terceira. In what became known as the Battle of Ponta Delgada, the two forces clashed on 26th July 1582 off the coast of present-day Vila Franca do Campo, on Sao Miguel.

Although the Spanish were outnumbered two to one, the improvised French fleet was defeated by their more experienced opponents. Antonio returned to the safety of Terceira, supported by a garrison in Angra of eight hundred French troops. Dom Filipe’s forces regrouped and returned in the spring in overwhelming numbers – ninety-eight ships and over fifteen-thousand men. His aim was to land an army; to take control of the fortresses lining the south coast and in doing so, take control of Terceira.

Antonio expected an attack to come from the sea via the main port at Angra – instead, the Spanish forces landed in the south east at Baia dos Mos where the defences were much weaker.

After just twenty-four hours of fighting, Terceira fell. The fortresses designed to protected the Azores now looked inwards – becoming barracks for the Spanish garrisons sent to control the islands’ rebellious inhabitants. With his rule now undisputed, Dom Filipe I and his descendants would rule Portugal and the Azores for the next sixty years.

Antonio & Elizabeth.

Antonio and a handful of his supporters fled to France, before fears of assassination by Dom Filipe’s spies drove him across the channel to England. After the failed attack by the Spanish Armada in 1588, ‘king in exile’ Antonio became a favourite in the royal court of Queen Elizabeth I.

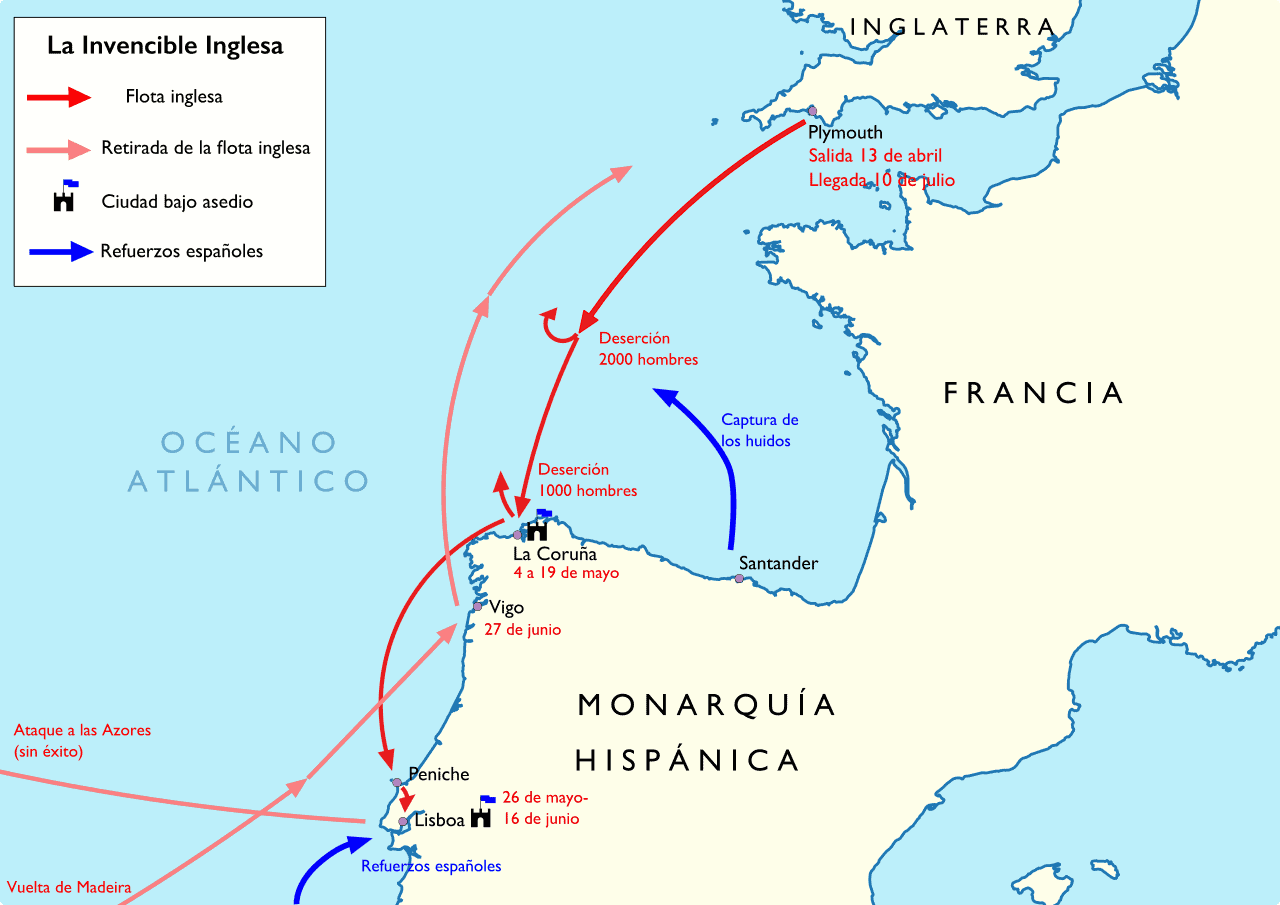

In 1589, Antonio agreed to accompany Sir Francis Drake on an English Counter-Armada. Their mission was threefold: to destroy the Spanish Atlantic fleet in harbour (freeing up Spanish-dominated trade routes), to incite rebellion against Spanish rule in Lisbon (restoring Antonio to the throne), and to establish a permanent English military base in the Azores (with the blessings of the restored Dom Antonio).

The expedition was an unmitigated failure on all counts. The core of the 1588 Spanish Armada had been made up of Portuguese galleons, which now lay in ports along the north coast of Spain – under repair following the battles of the previous year. Drake was reluctant to enter the Bay of Biscay for fear of capture, and bypassed Santander where the majority of the ships were being refitted.

Drake had also hoped Antonio’s presence would provoke an uprising amongst the population of Lisbon. Sailing up the Tagus, the English forces began their assault by destroying the city’s granaries and food supplies, turning the population against them. When the people failed to rise and without sufficient artillery to take the city, Drake moved on to the third phase of the expedition: establishing a base in the Azores.

Whilst the English forces had been assaulting Lisbon, the Spanish had been marshalling their ships just beyond the mouth of the River Tagus. Surprise was on their side and the damage they inflicted was sufficient for Drake to abandon his plans for the Azores. Not wanting to return home empty-handed, Drake headed out into the Atlantic in search of Spanish merchant ships, but had to console himself with a raid on the weakly defended Madeiran island of Porto Santo, before storms forced him to return to England.

Antonio lived out his days in France on a small pension from the French monarch Henry IV. He died in Paris on 26th August 1595 and was buried in the Convent of Cordeliers – present-day site of the Sorbonne University.

The Anglo-Spanish War.

With the Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of Windsor in abeyance, war comes to the Azores.

Operation Azores.

With King Felipe as the new head of state, Portugal became part of the vast Spanish Habsburg empire which included mainland Spain, the Canaries and Balearics, Sardinia, southern Italy, Sicily, the Netherlands, Croatia, Hungary, and vast tracts of North and South America. This ‘Iberian Union’ between the two countries had been long-sought after by the Spanish and long-fought against by the Portuguese.

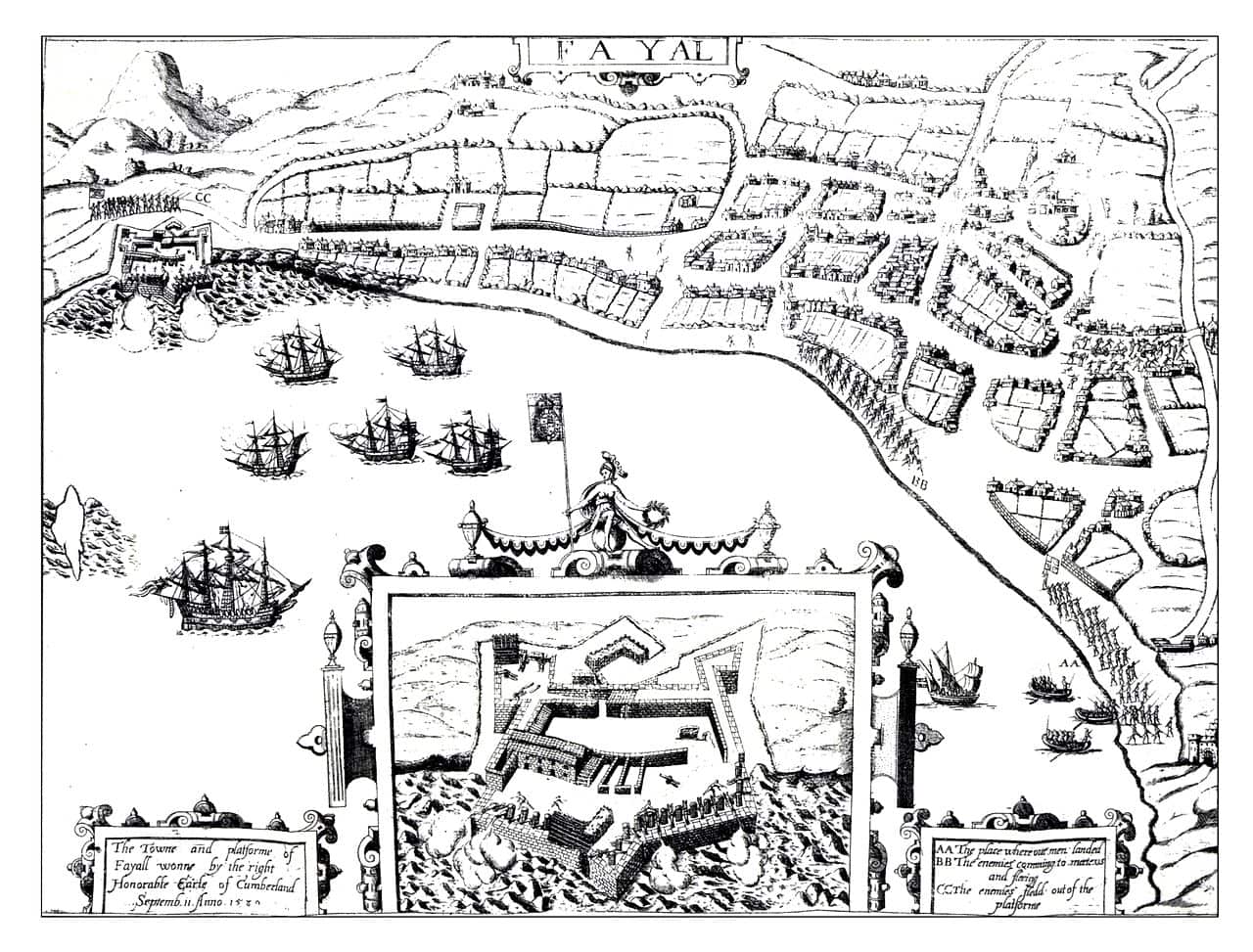

At the height of the Anglo-Spanish war (1585 to 1604), and with the country ‘demoted’ to merely a province of Spain, the long-standing peace treaties between Portugal and her oldest ally England were suspended. Spanish treasure ships were given a free reign across the Azores, and with King Felipe’s soldiers garrisoned in Azorean forts, the islands became a prized target for English privateers. Enter George Clifford: the 3rd Earl of Cumberland who, under the patronage of Queen Elizabeth I, wreaked havoc across the islands in 1589.

A year after battling the Spanish Armada in the English Channel, Cumberland set sail for the Azores on the Elisabeth Bonaventure with a plan to intercept and capture treasure ships returning from the Spanish Americas. Arriving in the Azores on 1st August, he began with an attack on the main island of Sao Miguel – flying a Spanish flag to gain entry to the harbour at Ponta Delgada, he sacked four Portuguese ships and made off with thirty casks of olive oil and Madeiran wine.

Attack on Angra.

Knowing the western-most islands were an important navigation point for ships arriving from the Americas, Cumberland headed west to Flores. He received word of a fleet of Spanish ships which had recently passed by en-route to Terceira. With the assistance of two additional English ships, the Barke of Lyme and the Margaret, he found the small fleet at anchor in Angra bay and attacked.

Monte Brasil’s natural protection helped make Angra a safe anchorage, but also created a bottleneck from which the Spanish ships struggled to escape. Eight ships were either captured or sunk, and Cumberland’s spoils included ivory, silver, gold, and porcelain from the Americas.

Horta under fire.

Cumberland’s next stop was Faial. Approaching the harbour at Horta under a flag of truce on 6th September, he demanded the immediate surrender of the fifty Spanish solders garrisoned at the heavily fortified Forte de Santa Cruz. When surrender wasn’t forthcoming and with the Margaret taking heavy canon fire from the fort, Cumberland sailed around the Ponta Espalamaca headland.

Safely out of range of the fort’s fifty-eight guns, he landed three hundred troops with orders to march on Horta. Homes, farmsteads and churches were ransacked over the following four days before the island’s governor Diego Gomez conceded to surrender.

The Forte de Santa Cruz was stripped of it’s armaments – these Spanish cannons were then brought to bear Cumberland’s next victim: the small island of Graciosa.

Raids on Graciosa and Santa Maria.

Unassuming Graciosa was at the very heart of Azorean food production in the 16th and 17th centuries, making it the perfect resupply point and target for Cumberland’s next attack.

At the height it’s agricultural output, the island had almost 14,000 residents – hard to believe if you visit present-day Graciosa with it’s population of just over 4000. You’ll find clues in the island’s architecture harking back to this time, particularly in the lavish interiors of some of the churches.

You’ll also see large ponds in the capital Santa Cruz – part of a complex network of reservoirs and underground aquaducts stretching across the island, transporting water to farms and residences. The Araucarua trees which surround the ponds were originally imported from Brazil – more evidence of the island’s far-reaching trade links.

With their supplies replenished, Cumberland turned his ships east to begin the voyage home. Unable to resist one final raid, they put into Vila da Porto on the easterly island of Santa Maria – to attack a Portuguese caravel en-route to Lisbon, laden with Brazilian sugar.

Vila’s high-sided harbour is an easily defended natural bottleneck, and the heavily-fortified Forte Sao Bras was ideally positioned to fend off a sea-borne attack. Under a barrage of canon and musket fire, rocks and missiles, Cumberland’s men quickly abandoned their attack.

He ordered the damaged Margaret to set sail for home with the captured Spanish ships from their Terceira raid in tow, before moving offshore and out of range of the Sao Bras’ guns. His wait was soon rewarded with the arrival of a second ship from Brazil, carrying 410 chests of sugar which they promptly stole.

It became apparent this was a convoy of three caravels, with lead ship the Nuestra Senora de Guia having already sailed from Vila some days before. Cumberland gave chase, catching and capturing the Senora de Guia two days later, before stripping her of her cargo.

Heading home.

With his holds full, Cumberland set sail for what was to be a disastrous voyage home. Hit by a series of intense storms, they struggled to catch the normally favourable south westerly winds. Supplies ran extremely low, and with no prospects for a resupply, many of the crew died from diseases exacerbated by thirst and hunger.

Cumberland finally made port in Falmouth on 27th December, where he was informed that the Magaret and the Nuestra Senora de Guia had both been shipwrecked off the Cornish coast – only six members from both their crews survived.

The Battle of Flores.

The most-famous engagement of this period occurred on 30th August 1597 – known as the Battle of Flores.

The English had assembled a fleet of twenty-two ships under the command of Thomas Howard, aiming to blockade the annual Spanish Treasure Fleet sailing from Havana to Seville. Receiving word of the plan, the Spanish dispatched a fleet of fifty-five ships to intercept – catching the English off-guard and ashore on the island of Flores.

Alerted to their approach from the east, Howard led the majority of the fleet north to safety. The English warship Revenge, under the command of Sir Richard Grenville, elected to stay and fight, allowing the rest of the fleet to escape.

Grenville had a reputation as a stubborn fighter and repelled boarders from five Spanish ships. After fifteen hours of fighting, the Revenge lost her mast and the surrendered. 150 of the crew were either killed or injured, including Grenville himself who died two days later.

Escaping the English, the Spanish Treasure Fleet set sail for home. Fifteen of the fleet’s vessels were lost in a severe storm off the coast of Terceira, including the Revenge which the Spanish commander Alonso de Bazan has claimed as a prize.

The engagment was immortalised by Tennyson in his poem The Revenge: A Ballad of the Fleet.

The end of Spanish rule.

Portugal was increasingly under pressure to contribute financially to the Spanish war effort. The Forte de Santa Cruz in Horta, and the Fortes Sao Sebastiao and Santo Antonio in Angra were all rebuilt, but at great cost to the local Portuguese nobility.

Matters were made worse as French and Dutch privateers joined the English in their attacks on Portugal’s merchant shipping. The Dutch West Indies Company were in dispute with both the Portuguese and Spanish regarding sugar exports from the Americas. The troubles came to a head in 1624 when Dutch Corsairs attacked the town of Vila Franca do Campo on Sao Miguel. The impacts from Dutch cannonballs are still visible today in the walls of Vila’s Igreja Matriz Sao Miguel Arcanjo church.

Tensions grew as war taxes grew, with anti-Castilian riots breaking out in the capital Lisbon. ‘Sebastianism’ began to spread amongst the general population: a nationalist movement based around the belief that Dom Sebastiao hadn’t died at the Battle of Alcacer el Kebir in 1578, and would return to reclaim his crown.

Under no delusions that Dom Sebastiao was alive but with the people on side, the Portuguese nobles devised a plan to take back the throne and their independence from Spain through their own ‘legitimate’ heir: the Duke of Braganza.

Coming soon…A brief history of the Azores Part Two: Restoration and the House of Braganza, the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake, Napoleon and Brazilian independence, the Liberal Wars, dissolution of the monarchy and the 1st Republic, the Estada Novo and the Carnation Revolution.

Archipelago Choice Azores specialists

We specialise in tailor-made holidays to the nine islands of the Azores. Our experienced team of specialists are ready to put together your personalised trip; just give them a call on 017687 721020.

Follow us online