Lucy Beney and her husband Charles returned to the Azores this summer after an eight-year absence, visiting the islands of Sao Miguel, Flores and Faial. During her stay on Faial, Lucy visited the western peninsula of Capelinhos: one of the Azores most-striking volcanic landscapes. Here’s what she found…

There are very few places on earth where we can look out on a wild and dramatic landscape only a decade or two older than ourselves – but Capelinhos, at the western end of Faial, is one of them.

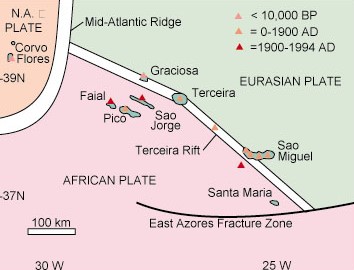

The Azores sit on the geologically active mid-Atlantic ridge. The Eastern and Central groups of islands – of which Faial is one – teeter on the edge of the European tectonic plate and experience some volcanic activity. The Western group clings to the edge of the American plate, and there has been no recorded volcanic activity there since their discovery in the fifteenth century. The plates are moving away from each other at a rate of about 2.5 centimetres per year, allowing for plenty of ongoing instability.

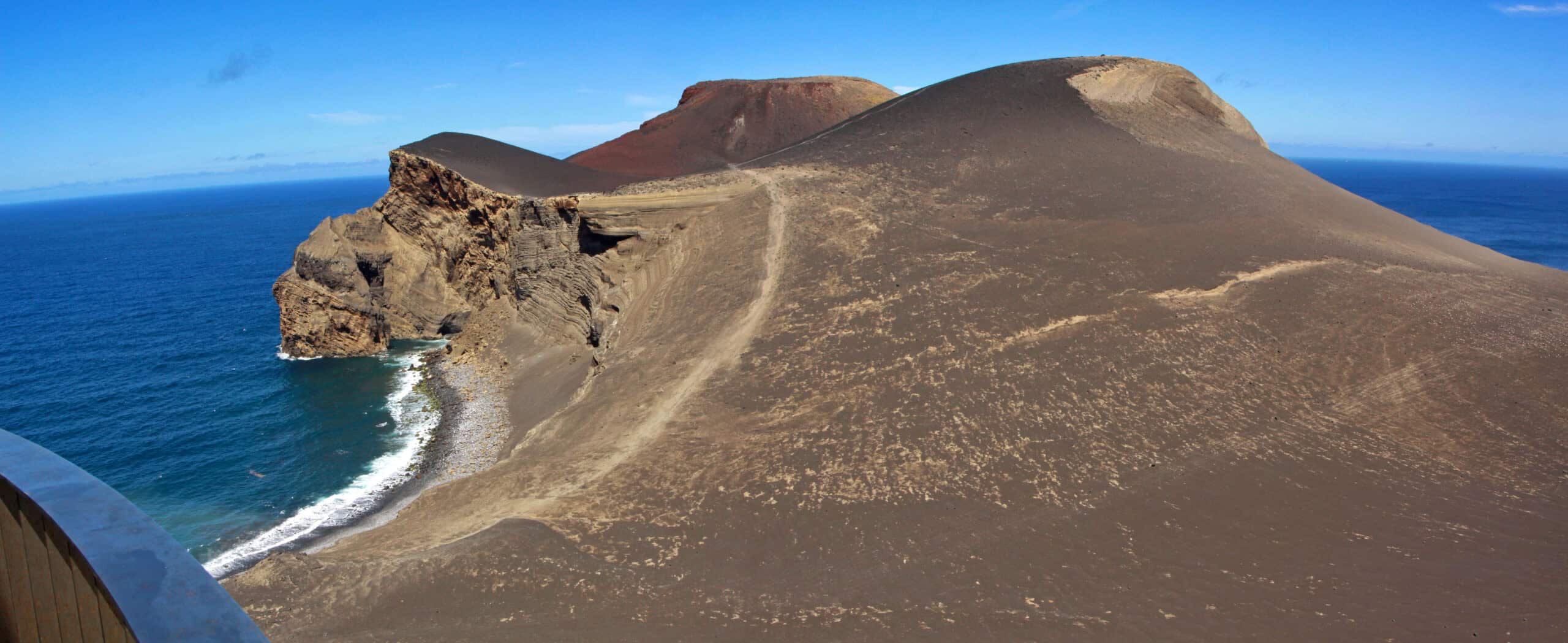

Between September 1957 and October 1958, the volcanic eruption at Capelinhos redrew Faial’s coastline, colouring it in with new sea cliffs and cinder beaches, all embracing the cone of the new volcano. These are not the spiky black lava fields of Hawaii or Iceland – this is something else entirely, and an overwhelming reason to visit this island.

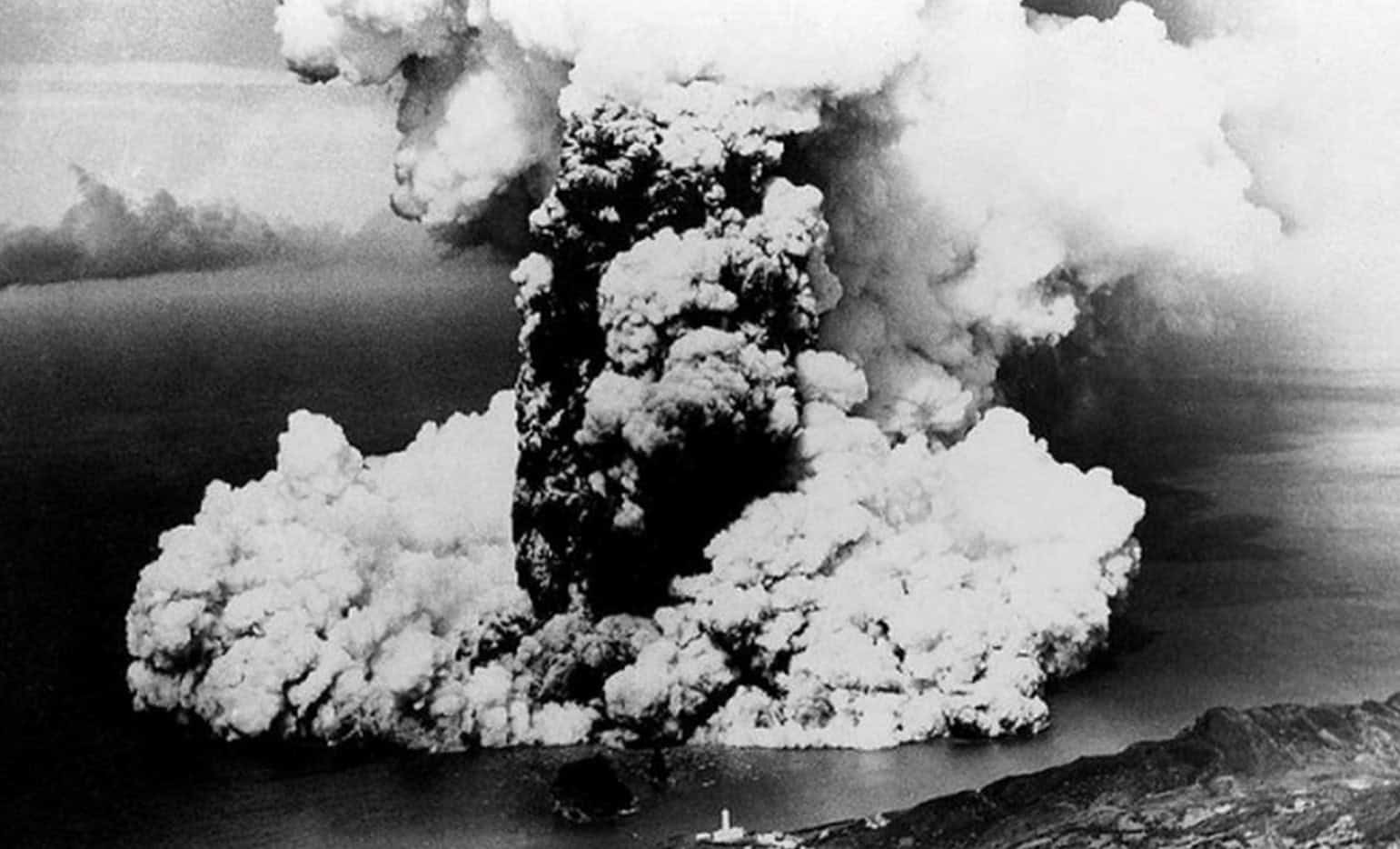

As summer gave way to autumn in 1957, whale watchers – who could earn extra income by alerting local whalers to the proximity of any of these magnificent mammals to the archipelago – spotted a strange phenomenon just off the coast. The sea appeared to be boiling. The lighthouse keeper, too, noticed something unusual. This was the start of one of the first volcanic eruptions to be rigorously and scientifically documented in real time.

Soon, the bubbling sea gave way to sky-high clouds of smoke, ash and water vapour, followed by fountains of molten lava. Having decided he would be safer sleeping elsewhere, incredibly, the lighthouse keeper returned to the site each day to record what was happening. At one time he had custody of seven different cameras with which to photograph the volcano, all provided by different press outlets in Portugal and abroad.

Frequently, he was joined by a local doctor, who was also an amateur geologist. Between them, samples were taken and geological activity observed which has greatly helped further our understanding of volcanic eruptions. The spectacular sight drew the fascinated and the fearful in equal numbers. Locals made weekend trips to Capelinhos to be photographed against a backdrop of nature’s fireworks, and the tours were arranged for visitors from far and wide. Simultaneously, statues were brought out from churches, and shrines were set up, while priests interceded for divine mercy.

The eruption entered a new phase in May 1958, when in the course of a few days, the island experienced 450 earthquakes of varying magnitude and the eruption threw lava 500 metres into the air. There was mounting concern that Caldeira Grande, Faial’s huge central volcano would erupt too, as the lakes in the bottom of its crater drained away under the enormous heat and pressure. Thankfully, that did not happen.

Astonishingly, nobody was killed during the thirteen months of the Capelinhos eruption, although there was immense destruction of property and farmland. Inevitably this had an ongoing effect on society and community life on the islands. In the United States, the Azorean Refugee Act was rushed through in 1958, and led to the emigration of around 1,500 people from Faial to start a new life on the far side of the Atlantic.

By that point, the island had grown by 2.4 square kilometres, as the cinder cone and isthmus formed from ash and lava became an integral part of the island. The lighthouse keeper’s beloved beacon now stands not on the coast but inland, buried in ash up to the first floor. Visitors can climb the twenty metres to the top of the tower, for a better idea of the magnitude of what happened during those tumultuous months, and still see the submerged rooftops of so many hurriedly abandoned homes and farms. Symbolically, steps at the entrance go down into the bottom of the tower, through layers of new land, before beginning the climb to the top.

The lighthouse, constructed in 1894, now forms an integral part of the award-winning Centro de Interpretacão do Vulcão dos Capelinhos – a highly informative, interactive museum, plus educational and scientific institution. This impressive, hands-on interpretation centre vividly tells the story of volcanoes, igneous geology and plate tectonics, through the birth of the Azores and other volcanic islands around the world, to the Capelinhos eruption. Contemporary footage, photographs and newspaper cuttings bring the accounts to life. Numerous lava bombs testify to the destructive power of the eruption.

Interestingly, posters advertising events to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the eruption clearly demonstrate the way the landscape continues to change. The new promontory – which is now the westernmost point of the Eurasian tectonic plate – looks different with each passing decade, as wind and waves work their magic.

A video about the volcano produced by TAP, the Portuguese airline, declares “from a natural catastrophe, Capelinhos became a place of contemplation”. While “contemplation” frequently has a peaceful ring to it, it would be hard to visit Capelinhos and not pause to reflect on the awesome power of nature, on how the destructive and the creative work hand-in-hand and on the continuing constant motion of a world in which we live.

Capelinhos now rises starkly from the sea, a modern moonscape of rock and ash, continually shape-shifting. Gradually a seasonal green haze of vegetation is softening the contours of the land, and one day it will be indistinguishable from the rest of Faial. For now, though, it is quite unlike anywhere else. Go – walk the trails, climb the lighthouse, test your knowledge in the interpretation centre. Above all, stand still and wonder at the power of nature.

Follow us online